We make decision’s every day of our lives, from the simplest decision about what to eat for breakfast or what to wear when we go out, to more complex problem solving decisions such as how to overcome an particular obstacle that is preventing us achieving a particular goal, or which choice of investment will provide the best return.

What is decision making?

Decision making refers to making choices between alternative courses of action. This involves a comparative assessment of the costs and benefits of different courses of action, however the future value of a choice is not always fixed or known before it is made. This means we can only make most decisions based on a “best guess” basis. So there is a level of risk associated with most of the decisions we make, particularly the important ones.

There are many factors that play into our decision making process, and the subsequent choices we opt for. Here is a breakdown of those factors.

Risk Taking

Risk taking refers to decision making when the outcomes of particular choices are not guaranteed, and the consequent uncertainty means that an assessment of the probability (chance) of a positive or negative outcome has to occur. Given that human thinking about probability is prone to many errors and biases, there are many important practical implications for risk taking behaviour. We will discuss many of these errors later.

We are constantly assessing the risks against the rewards of taking any particular course of action, especially if it’s an important decision. We have a tendency, as human beings, to prefer safety over risk and will often favour the status quo over action that has the potential of opening us up to risk, danger and uncertainty.

To overcome this bias we have to find the NEED, or WANT within us, to motivate us enough to take the risk, effectively swinging the balance in favour of action over settling for the status quo.

Choice Architecture

Choice architecture is the design of different ways in which choices can be presented to consumers, and the impact of that presentation on consumer decision-making. It’s the fact people are more likely to op-in to something rather than opt-out, if the default value is already the opt-in option and vise versa.

How things are presented to us has a greater impact on our choices than we realise. Big businesses have long since known this and set things up for their advantage, making the most of our natural tendencies and dispositions.

It’s important to realise that the creators of the modern world, are not necessarily designing things with our best interests at heart, and we should, at least, be aware of the possibility of manipulation from other parties.

For example, social media is designed to keep us hooked and coming back for more, red notification bubbles tap into our innate sense of curiosity, knowing we won’t be able to resist finding out what’s waiting for us on the other side of that click.

Inner conflict between WANT and SHOULD

This is the inner conflict between;

- What do I want?

- What should I choose? what we ought to choose

If you’ve ever struggled with your weight, this scenario will be very familiar to you. You want that delicious looking chocolate cake, rather than the salad, but you know you should, for the good of your health, choose the salad.

Facing these kinds of choices, uses up your willpower, which will eventually run out and you’ll succumb to the temptations. So remove the temptations or remove yourself from them.

This approach also goes for distractions. If you’re productivity is being adversely affected by your Facebook activities, lock your phone away or lock yourself in a room free of social media connectivity, until your work is done.

Influence of beliefs and values

This is a biggie and I’m not going to go too deep into beliefs and values here, other than highlight their importance.

All behaviours are a reflection of our thoughts, and thoughts that are repetitive, fixed, and invested with a sense of ourselves, are what we call BELIEFS, they are our beliefs. Conditions and rules that are attached to these beliefs become our VALUES.

Beliefs in particular shape how we behaviour, how we interact with other people and the world around us. They affect our affiliations, or passions, what we pay attention to, what we buy, and how we live our lives.

Much of our beliefs come from social conditioning, they are largely built form assumptions, and inferences, rather than facts and evidence. They are stories we tell ourselves to make sense of the world around us.

We look to confirm our beliefs, ignoring or rejecting counter-argument, rather than trying to disprove them, which is the scientific approach. This is what is described as confirmation bias, if you want to find out more about it.

The best way to deal with beliefs and values is to question their origin, their basis and accuracy. It’s much more productive to consider beliefs as hypotheses, which you look to disprove rather than prove, like science does.

If you can’t prove something, consider it a best guess, until more evidence is discovered.

Avoid throwing your opinions and views around, until you know for sure what you’re talking about.

If someone tells you something ask “how do you know?”, and “where is the evidence?”

Unknown consequences and outcomes

Many decisions are made with knowing what the consequences or outcomes will be. Sometimes we just can’t know whether choice A is going to be better than choice B.

We should instead weigh the facts, as we know them at the time, and commit to whatever choice we make and make the best of it, living with the consequences.

We are not passive recipients of the decisions we make, we interact and influence them as time progresses. So by committing to them and stopping questioning and second guessing ourselves, we give ourselves the best chance of getting the results we are looking for.

Choice overload, too many choices

Too many choices can be paralyzing, and results in nothing being chosen, so be wary of thinking more options are better.

Difficulty in evaluating and comparing choices

It can often be difficult to pick one choice over another because they offer different advantages and disadvantages.

It helps to have a goal that you’re working towards, and decide which is most likely to get you closer to it. That way you have a direction you’re heading towards. But even then some things might just not comparable so what do you do in such circumstances?

Well you decide on one based on the facts, and commit to it.

Errors in THINKING

Dealt with below.

How to too make better decisions

We would all like to know how to do exactly the right thing at all possible times, making good decisions in all circumstances. Some help was given to us back in 1738 by Daniel Bernoulli. The equation he came up with has been translated as:

The goodness we can count on getting from a decision we make, which is based on:

- The odds of gain

- The value of that gain

Expected value = (odds of gain) x (value of gain)

In itself this equation offers an effective decision making framework, but we must be wary of miscalculating the odds of gain, and be mindful about how we value that gain when using it. As long as we sidestep the many errors and biases in our thinking (which we”ll discuss below), we should be good to go.

Much of our decision making, depends on us using memory and comparison in our assessment of PROBABILITY (when we’re working out the odds of gain) and likewise when trying to establish the VALUE of that gain.

For example, if I asked you, would you consider buying a burger for £10. You would likely make an assessment about what else could be purchased for the £10, along with checking your memory to see what you had paid for a similar burger in the past. If you considered the burger to be overpriced, you would likely not purchase, if you believed there to be other things more worthy to spend the money on, you may opt for them instead. What you’re doing here is you’re making use of comparison and memory to determine the burgers value.

Other factors also come into play, for instance, if you’re hungry you’re more likely to opt to buy the burger. How I frame the question, might also impact your answer. If all your friends were buying a burger, you might decide to buy, just to fit in. If you knew you weren’t going to get the chance to eat for a prolonged time afterwards you might again, opt to buy.

So while this is a pretty straight forward decision, to buy or not, there are still a lot of potential factors that come into play. Decision making is not always so clear cut, particularly if there are a number of choices available.

Let’s look at some of the pitfalls that can befall us if we’re not careful, they consist of errors in judgement and personal biases.

Memory Errors

Let’s look at a couple potential errors in memory…

If I asked you “What is most common, dogs on leashes or pigs on leashes?”. You would most likely say dogs, largely because you have seen and remember seeing more dogs on leashes than pigs on leashes and because of this, memory is relied upon as more representative of fact. You are likely to be correct in your assessment, but unless you’re an authority about the world of pigs, and pig owners, you could easily be wrong.

If I asked you “Which is more common in the English language, words containing the letter “R” in first place or in third place?” You would probably be able to remember more words with the letter “R” in first place and would likely choose this as a result, when in fact there are more words with the letter “R” in third place. Because these are harder to recall we have a tendency to think there is less of them. These are examples of “Availability heuristic”.

Comparison Errors

Lets look at couple of examples of errors when we try to compare things,…

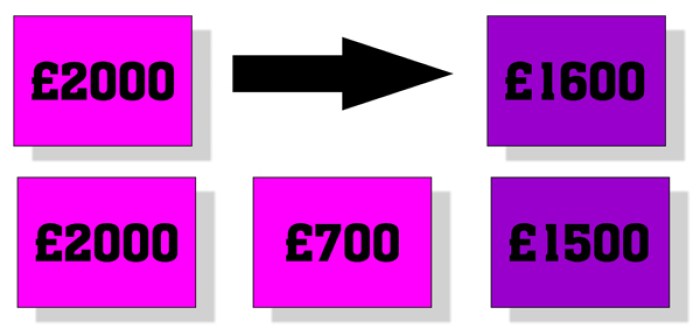

A £2000 Hawaiian vacation package is on sale for £700. You think it over for a week, but by the time you get to the ticket agency, the best fares are gone and the package will now cost you £1500. Would you buy it? Most people would say no. because they would not want to pay for something that was cheaper just a week before, even though the vacation is still well priced at £1500. If the price had just gone from £2000 directly to £1600 (without the drop to £700 in between) would you feel any differently even though the holiday is in fact £100 dearer in the second scenario? Many people would be inclined to opt for this situation given the choice.

Another example for you to consider. You are on your way to the theatre. In your wallet you have a ticket for which you paid £20, along with a £20 pound note. When you arrive at the theatre you discover that you’ve somehow lost the ticket. Would you spend your remaining £20 on a new ticket? Most people answer no. Let’s change the scenario and replace the ticket with another £20 note instead, so you now have two £20 pound notes, and this time you lose one of the £20 pound notes. In this circumstance people often change their answer to yes. Why is this? Well in the first scenario they say they do not want to pay twice for the same ticket, in the second scenario they take the opinion that just because they have lost £20, what difference does it make, they came to see the show and still want to see it.

In our last example, imagine you went to your local cinema and saw a small portion of popcorn for £3 and a large for £7, which would you choose? If a medium portion was then added for £6.50, which would you go for now? In tests, when the medium option was added, more people opted for the large portion than before, why? Because in comparison to the medium the large looked better value than it did before.

So you can see from these examples how easily errors can occur when relying on memory and comparison.

Poor assessment of Probability

Lets look at how our assessment of probability can result in bad decision making. There are two methods we use to assess probability these are:

- “Representativeness heuristic” refers to estimating the probability of a particular sample of events based on their similarity to characteristics we feel are typical of the whole category population of those events. This may result in thinking some events are more likely than others, and that certain trends can be predicted. But if people fail to follow the true principles of representativeness, such as ignoring information on probability base rates or forgetting that small samples are less likely to be representative, then this can lead to false estimates as is seen with use of stereotyping. For example if we toss a coin, a sequence of HTTHTH is thought to be more probable than a sequence of HHHHH, even through they are equally likely

- and secondly “Availability heuristic” (examples given previously) is based on estimating the probability of an event based on how easy it is to remember. This may lead to familiar, recent or popularised events being more available in memory and subsequently seen as more probable. For example murder might be thought to be more likely than other crimes because of its greater media coverage.

Faulty decision making

Rational decision making would involve taking account only of the odds of an expected outcome and expected value gain of each option. In fact, this is rarely the case, and is often influenced by some of these biases and errors in thinking:

- Framing effects – how the problem is presented to us. This is particularly so with marketing messages and political messages which are aimed at getting us to react in a particular way. The way the information is presented often intensifies certain facts and downplays others, in the hope of pushing us towards a certain course of action. (check out our post on Hugh Rank’s Persuasion model)

- Loss aversion – as humans we are wired through evolution to be more sensitive to loss than gain. As a result we want to protect what we have over reaching for more.

- Elimination-by-aspects theory – this involves eliminating options by considering one relevant attribute after another.

- Satisficing theory – choosing an option that has satisfactory attributes when it becomes available. Most commonly found when dating, we pick the first suitable mate that comes along, often rejecting others that come later, but that might be a better suit.

- Conforming evidence trap – which involves seeking out evidence that justifies our choices and subconsciously ignoring contradictory evidence rather than looking at the whole picture.

- The status quo trap – shifting deck chairs on the Titanic rather than jumping over while it’s sinking

- The sunk cost trap – which involves throwing good money after bad in the hope of recovering losses rather than simply cutting losses, as evidenced by many gamblers and stock market investors.

- Trial and error – where no decision can be considered correct unless it has been subjected to testing and scrutiny in order to accept or reject it. Which appears to be a rational approach, but is prone to subjectivity and influenced by the persons own values.

A few more to consider:

- Compensatory rule – “we selected the security system that came out best when we balance the good ratings against the bad ratings”

- Conjunctive rule – “we picked the security system that had no bad features”

- Disjunctive rule – “we selected the security system that excelled in at least one attribute”

- Lexicographic rule – “we looked at the feature that was most important to us and chose the security system that ranked highest on that attribute”

- Affect referral rule – “everything they do is outstanding, so we decided to have them install our security system.”

Biases with Time

Time also plays a part in our decision making:

- If I offered you £60 now or £50 now, you would likely go for £60 now.

2.If I offered you £60 now or £60 in a month most would go for the £60 now.

3.If I offered you £50 now or £60 in a month most would go for £50 now – because they don’t want to delay gratification.

4.If I offered you £50 in 12 months or £60 in 13 months many would elect to go for the £60 in 13 months because they think to themselves, what’s the difference between 12 or 13 months, I might as well hang on for another month and pocket an extra £10. But in reality the only thing that has changed between our third example and this one, is the time frame, and the fact that it is further away from the present moment. When we actually get to month 12 we will probably change our minds and wonder why we didn’t settle for the £50 in 12 months rather than wait and extra month for the extra £10.

What else plays a part in poor decision making outcomes

Decisions are made with our best interests at heart, and with positive intent, however we don’t always get them right as discussed. This is partly due to the “faulty thinking” we have talked about above but also other things play a part

- External influences and pressure forcing our hand or influencing our decision making, such as time limit, peer pressure, salesmanship, fraudsters, threat

- Luck plays a part in the final outcomes and we shouldn’t underestimate its role.

- Unforeseen events and circumstances outside our knowledge at the time of the decision or after a decision is made. Unless we have a magic wand, there is little we can do about this. “With hindsight I would have….”

Deductive and Inductive Reasoning

We have included reasoning as part of this discussion on decision making, to highlight how we can easily stray away from accurate thinking, which can later impact our decision making effectiveness.

“Reason sits firm and holds the reins, and she will not let the feelings burst away and hurry her to wild chasms. The passions may rage furiously, like true heathens, as they are; and the desires may imagine all sorts of vain things: but judgement shall still have the last word in every argument, and the casting vote in every decision.”

— Charlotte Brontë

Reasoning or accurate thinking, as it is sometimes described, most commonly comes in the form of Deductive and Inductive reasoning and is often used in the search to find logical explanations for things around us. Why does this happen? How can I make this happen?

Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning – is an hypothesis or idea about things we don’t know. It is built on arguments that do not have categorical support for the conclusion. We make many observations, discern a pattern, make a generalization, and infer an explanation or a theory. An example of inductive reasoning is:

Lots of people are interested in internet marketing, Mr Turner is a person, so Mr Turner likes internet marketing

The premise that “lots of people are interested in internet marketing” is true, as is “Mr Turner is a person”. The conclusion that follows “Mr Turner likes internet marketing” is logically correct, but may not be true. The reason for this is that while we have stated that lots of people are interested in internet marketing, Mr Turner may not be one of them.

Because inductive reasoning is based upon probabilities, conclusions are considered to be cogent, rather than true. This is because the probability exists that the two accepted premises may not truly lead to the acceptable conclusion.

Deductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning on the other hand is when we have the facts or appear to have the facts and the arguments provide absolute support for the conclusion.

Deductive reasoning makes the strong assertion that the conclusion must follow the premises out of strict necessity. Denying the conclusion means that at least one of the premises is self-contradictory and thus not true. For example:

All human beings need oxygen to survive. Mike is a human being, therefore, Mike needs oxygen to survive.

For deductive reasoning to be effective the original premise needs to be true, as with the example used above. However check out the example below. Although the conclusion follows on logically from the premise, there is possible doubt over the validity of the original premise that “Every website that has an opt-in form on it, is collecting subscribers”. If this premise is invalid, the conclusion will also be invalid.

Every website that has an opt-in form on it is collecting subscribers, if I put an opt-in form on my website, I will get subscribers.

So the key to a creditable conclusion lies in the premise. If this is valid then so will the conclusion, if not, then neither will be the conclusion.

Another form of deductive reasoning is the Syllogism. A Syllogism consists of a minor premise and major premise and a conclusion and are of the form If A=B; and B=C; then A=C.

A=B (minor premise/specific instance) i.e. Patch is a dog

B=C (major premise/generalisation) i.e. All dogs can bark

A=C (conclusion) i.e. Patch can bark

There are a number of Syllogism fallacies that can producing faulty conclusions these include;

- undistributed middle – some dogs (rather than all)

- illicit major – last part (C) of the conclusion is broader than premise allows

- illicit minor – first part (A) of the conclusion is broader than premise allows

Check out this article for a more in-depth analysis of Reasoning.

So as you can see, it is easy for poor reasoning techniques to impact our decision making effectiveness, and we should always be mindful of ensuring we are using accurate thinking in our decision making.

So as you can see there are many ways of making bad decisions. Below are more tactics designed at improving decision making.

Common Decision Making Methodology

There are often 3 levels of decision making that are generally employed:

- The simplest THE REFLEX ACTION (knee jerk reaction. Unconscious, without considering the alternatives i.e. profits down – costs need to be reduced, or sales are slipping – prices too high. Here is a great example. A racket and ball together cost £1.10, Racket costs £1 more than ball, how much is the Racket? work this out for yourself, most people say £1, the answer is actually £1.05.

- ALGORITHM or checklist. i.e. You come face to face with a tiger, You instantly go into flight or fight mode. You’re mind within a nano second asks itself, is it a big one? If the answer is yes, you run, if no, you ask yourself, do I have spear with me? If yes you might fight, if no, you run.

- Using more sophisticated methods like, Cost Benefit Analysis and The decision matrix approach. Which involves listing alternatives and weighing the pros and cons of each, scoring them against each other and choosing the winner (see worksheet at bottom of post).

As individuals we usually make decisions using the first 2 of these. The first (Reflex action) is not recommended in most cases other than were you have no choice such as flight or fight/life or death situations. The second (Algorithm or checklist) takes the hastiness out of the situation and can help you to be more logical in your thought process. Most of the time we make decisions using our emotions and feelings and this can cause us all sorts of problems, it’s best to give yourself some space to remove the emotion from the situation and consider rationally the best course of action to take.The third option (decision matrix) discussed above is much more considered and allows analysis of the alternatives, but is likely to be biased by subjective preferences. You can ask for a second opinion as a type of check and balance, to help correct this.

More decision making tactics

- Identify all factors that affect a decision (weight them against one another) for instance Cost versus Comfort plus emotional factors such as attractiveness felt by having/wearing etc. avoid letting emotions affect decisions. Write down the options and canvas opinion from trusted others.

- Be aware of your perception of loss or gain. For instance offering people £20 or giving them £50, taking back £30 and offering a bet to win back the other £30. This framing effect will result in more people taking the latter option even though they would be getting the same thing. People will make bolder decisions to avoid loss (loss aversion)

- We tend to post-rationalise decisions after the event. Avoid dressing up bad decisions.

- Be aware of Priming – images/words/temperature/smells can colour peoples decisions later on. For example getting people to hold a hot drink can illicit warmer feelings towards someone soon after. So be aware of others trying to manipulate us.

- Recognise intuition.

- Use a two-tiered approach with a small group of core people who set the standards that a larger group can implement with autonomy but within those standards

- Tap into as much knowledge as possible (mentors and mastermind groups)

- Ensure those carrying out the decisions are involved in the decision making process.

Harvard Business Review blog recommends using the Trick acronym to aid decision making.

- Two – tiered approach (detailed above)

- Rapport with strategic team and implementers

- Involve all – from management to customer in the decision making process

- Cause and effect reversals – to remove self limiting beliefs that are effecting how you approach strategy. i.e. Is your strategy impacting your success, or is you success impacting your strategy?

- Kahneman perspective – 12 question checklist to identify and reduce bias

Accurate Thinking

In his book “Think and Grow Rich” by Napoleon Hill he describes the using accurate thinking as being the foundation of all successful achievements.

He advises to separate important facts from unimportant facts. An important fact is one that aids you in the achievement of your goal, if it doesn’t do this consider it unimportant.

Be wary of opinions prejudice and biases that come with them. Look for proof of hard facts. Ask “How do you know?” and stand firm until they have answered to your satisfaction.

If someone has a negative attitude about someone or something, be wary of what they say because it is sure to be negatively framed.

- Free advice is usually worth what it costs

- Never accept anything as fact until proven

- Negative attitude = negative framing

- Don’t give away what you want the answer to be when you ask a question, cause people want to give people what they think they want to hear

- Ask “how do you know” when you can’t identify if something is true

Check out his book on Amazon by clicking on the image below.

Conclusion

Personally I like to use the “Decision Making Matrix” template below and get other people involved to get some perspective and offset some of my biases. while it has served me well, I would suggest finding what works best for you, however if you check out my post on problem solving you will find a large list of tools and techniques to help in your decision making.

I suspect the biggest takeaway from this post will be in identifying the biases and errors in thinking that may affect many of the day to day decisions that you make. Hopefully by being more aware of these you will look more critically at the decisions you make and what might be motivating them. Decision’s are mainly made on a best guess basis and are sometimes influenced by factors outside our control and span of knowledge at the time we make them. We can only control the actions we take and by examining our biases and errors in thinking, try to improve our decision making strategies.

When we think about things in the distance future we have a view of them, but as we move closer to them we change our minds. Our brains have evolved from a very different world, where we needed immediate gratification to survive. We need to be more aware of these old habits which are no longer relevant to our modern way of living, and be more willing or open to, delaying gratification.

For a working excel spreadsheet version of the form above please join my mailing list. All the calculations are done for you, just enter your own data.

Check out our PROBLEM SOLVING posts.

For more articles about DECISION MAKING, click here.

Update 26/10/18

I came about this Ted talk about how to make difficult decisions, I thought I would add it to this article because I thought it would provide great value.